In July, I graduated from the University of Oxford with a master’s degree in Earth Sciences. Studying our Earth reveals the complexities between its systems across time and space. Anthropogenic climate change exploits just how interconnected those systems are, and research suggests we are on schedule only to upset the balance further. Society needs more Earth Scientists to unravel and understand the intricacies of our planet to help individuals and governments alike tackle the globally pressing issue of climate change.

1. Earth is a beautiful, but complex and delicate system of systems. We threaten the balance between them.

Our Earth is a complex system of interconnected systems all in delicate balance from the minute scale of the sub-atomic world right up to the majesty of our Solar System. Studying Earth Sciences means considering the intricate Earth System at all scales and across time.

Clear across all Earth Science disciplines is that, under the pressing context of modern climate change, connections between systems create a dilemma: perturbations we cause will have far-reaching consequences. For example, plastic waste charged into the world’s oceans is not only an eyesore, it causes upset to marine ecosystems, species loss, and even feeds back on poor human health. Earth’s oceans may rebound to their natural state over geological time – the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission reports that it takes 500-1000 years for most plastics in the ocean to degrade – but that may be too late for many species already under immediate environmental stress.

In so many ways, humans have deeply upset the delicate balance between the planet and its inhabitants, including our own. But in what ways has Earth Sciences revealed this?

2. Earth has vast expanses of time, but human activity is accelerating planetary processes with immediate, time-sensitive consequences.

Earth is a dynamic place across time, deep time, which can be difficult for the human mind to comprehend. We generally think on timeframes significant to the timespans of our lives and civilisations. Seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, and years, sometimes centuries and millennia. Studying Earth Sciences, you quickly become accustomed to thinking of a million years as mere milliseconds: a geological blink-of-an-eye, nothing compared to the 100s of millions of years it takes the Earth to churn crystals round the convection cells in its mantle, or gradually uplift, metamorphose, and erode mountain belts, or transport plants seeds across drifting currents and continents to new lands where they might colonise and speciate.

Of course, there are much faster processes too, like the melting of ice sheets over the many pulsed, rapid deglaciations of the ice ages of the last 800,000 years. These natural, continental-scale melting events probably occurred on the of-order 10,000-year timescales controlled by gradual, cyclical changes in Earth’s orbit.

However, what’s worrying now is the effect of human activities on the rates of natural planetary processes. In digging incessantly for fuel and resources to power our rapid-fire lives and greedy, not green, cities, humans have pumped carbon that was stored over millions of years into Earth’s atmosphere over only several decades. In doing so we have unquestionably smothered ourselves with an unprecedented layer of insulation that has completely knocked the planet from its natural equilibrium state. This means faster deglaciation rates, leading to faster rates of surface erosion, increased risk of flooding, terrestrial habitat loss, offset river water and sediment discharges into the world’s oceans, upsetting natural oceanic currents in our already warmer and acidified waters.

These positive (i.e., accelerating) feedbacks also lead to greater risks from natural hazards like wildfires, landslides, tropical storms, and storm surges with frequencies of occurrence that exceed their geological background levels. And, with more of us living in cities than ever before, cities that consume vast quantities of natural resources, we inhibit the resilience of natural systems to respond to environmental perturbations that could otherwise help protect us. Cities suppress the natural routing of river courses; they uproot huge, areal expanses of green land: trees, meadows, and their wild inhabitants, and they incubate the local built environment by up to 9 degrees Celsius, as exemplified by this tweet from Trees for Cities.

Humans have rocked Earth’s natural processes so far out of balance that even the enormous scale of the planet itself cannot keep up with our systemic reckoning against it. Our actions have already produced time-sensitive consequences, which will take 1000s of years-worth of invested efforts to reverse, which need to occur within our lifetimes.

3. Hysteresis: Earth has a climate memory, storing temperature perturbations in the global ocean for generations.

Earth’s temporal backstory is important for understanding its present state. Studying palaeoclimates (climate states of the geological past), it becomes clear that hysteresis exists strongly in the Earth system. Former climate states, especially their temperatures, can inform future climate states. ‘Climate lag’ means there is a delay between the causes and effects of global temperature change. Estimates for the anthropogenic climate lag time range from one to several decades, and evidence from climate modelling suggests that the lag time increases with the strength of the driving force of the temperature increase.

Why is this significant, and terrifying, news for us? Well, it means that freakish environmental phenomena and the effects of climate change we are witnessing now: raging wildfires, abnormal weather patterns, more intense tropical storms, heightened seasonal contrasts, and droughts like the one that decimated crops and grasslands in Europe this summer, are likely not caused by current carbon emissions. Instead, they are likely the response of the climate system to carbon emissions produced 10 years ago, or longer. Therefore, the environmental impacts of rising atmospheric CO2 and methane levels today will possibly not be observed for decades to come. Our descendants for the next one to two generations will have to deal with the climate chaos wrought by our generation if do not take decisive action now. And they’ll have to do so almost certainly with fewer resources since we’ve stripped the land of many of its assets already.

However, the climate lag time is not the same everywhere. Some regions may not see the full effects of climate change until much later when global mean temperatures are higher still. Scientists studying Dansgaard–Oeschger events (rapid warming events) of the last glacial period found that, on average, Antarctic temperatures lagged 218 ± 92 years behind Greenland temperatures. This is because the global ocean transfers heat from north-to-south by means of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC for short. Essentially, it takes time for heat entering the northern polar regions via the Gulf Stream to be circulated at depth to the southern polar regions around Antarctica where delayed melting of the Antarctic Ice Sheet may be encouraged.

Translating this to our present, anthropogenic warming event, the research indicates that it may take centuries for warming in the Northern Hemisphere to fully translate to warming in the Southern Hemisphere. The lag time may lengthen still with the ‘very likely’ chance that the AMOC will weaken or slow-down over the 21st century, as given in this 2019 report by the IPCC. Of course, some melting of the Antarctic Ice Sheet has already begun, which we see in the rapid retreat of glaciers and the instability of ice sheets on the west of the continent and on the Antarctic Peninsula (*queue Frozen Planet II*), but this is mostly a response to warmer surface temperatures. Adding the effects of delayed heat transfer via the AMOC, the picture generated for the polar ice sheets and global climate looks very bleak.

If we wish to spare our natural environment and future generations this fate, we need serious, widespread, and invested action in capture carbon and storage (CCS) technologies to reverse decades of carbon emissions. However, even if we did employ cutting-edge CCS today, much of the damage humans have already caused is irreversible – check out this video to find out why. Therefore, responding to climate lag is, to an extent, an impossible challenge, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do our best to prevent the worst-case scenario from happening.

4. Earth Sciences is crucial for reaching the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

In 2020, I spent some time long-distance volunteering (it was 2020, after all) for the Oxford branch of Geology for Global Development, a charity invested in promoting awareness of the role of Geology in meeting the United Nations’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). My involvement led to arranging a talk (albeit online) presented by Dr Sophie Gill, then researching how coccolithophores – important calcium carbonate microbes in the ocean – might be able to help us work towards SDG #13: Climate Action. Sophie’s research was exploring the possibility of enhancing the ocean’s natural alkalinity to encourage greater uptake of CO2 dissolving into the ocean from the atmosphere by coccolithophores. The technique would, in theory, help buffer against ocean acidification and coral bleaching, and assist with direct carbon capture and storage (CCS) performed at fossil fuel power plants. Research into different methods of carbon dioxide removal (CDR), which includes practices like reforestation, regeneration of peatlands, and geological injection of carbon into the subsurface, are ongoing, but the talk highlighted for me how clever use of geological techniques might help us to engineer smart solutions to the climate crisis.

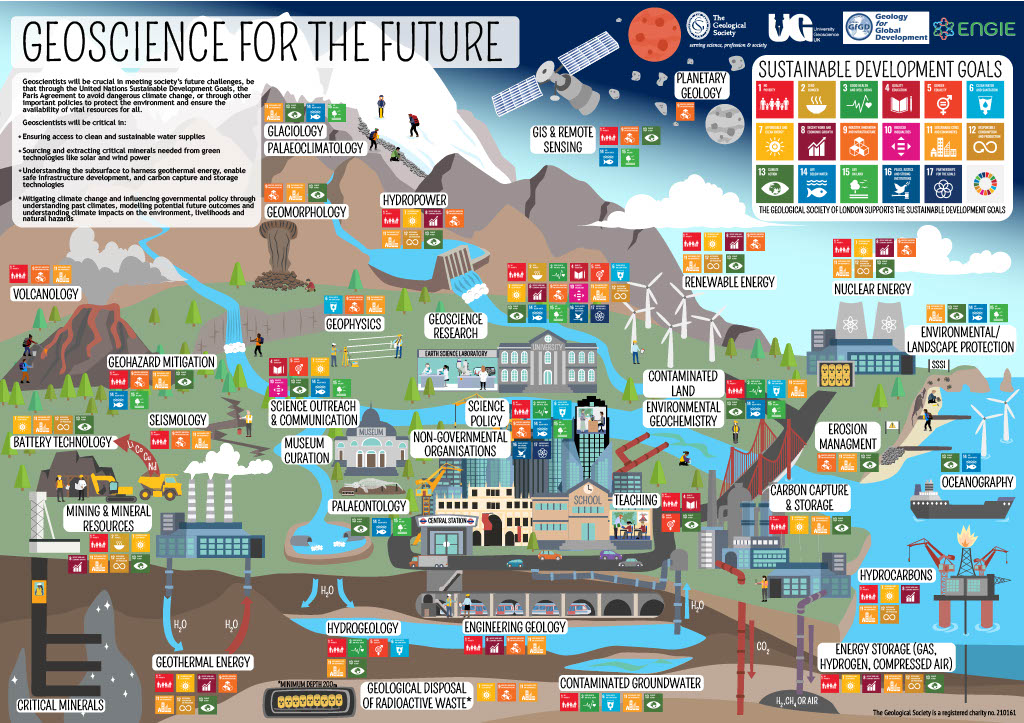

The Geological Society of London also testifies how important Earth Sciences is for meeting the SDGs, and aid in the green transition. The many subdisciplines of the subject lend themselves to tackling many geological and earth-related engineering problems of the industrialised world, such as those in the poster below. Every geologist has a role to play. The only question is which issue to tackle?

5. Society needs more Earth Scientists to contextualise Earth’s past in order to predict Earth’s future.

As should be clear by now, Earth Sciences uses geological evidence to peer into the deep past. Understanding how the Earth operated eons ago provides Earth Scientists with data with which to calibrate geological processes and events of the present, and future possibilities. For fields like Climate Science that are of pressing, societal importance, the more that can be learnt from the past, the more accurate the picture that can be modelled of the future. However, what was once is not necessarily what will always be. The unique configuration of the continents between geological periods, which is closely linked to global climate, is a good example of this. So, Earth Scientists must navigate carefully between what was and what could be whilst accounting for the large uncertainties that come with determining the state of the Earth across multiple of its interconnected systems potentially millions of years ago. With so much time and space to cover, it’s no wonder that every research paper finishes with some variant of: “Our results show [insert findings here], but we need more data.”

Earth Sciences is a disastrously underappreciated and understudied subject compared to other science subjects like Physics, Chemistry, or even Psychology. Why is this? I think at the heart of the issue is that Earth Sciences is insufficiently taught in schools. Primary school children are famously fascinated by space, dinosaurs, volcanoes, and sea creatures. Studying Earth Sciences, you encounter all of these exciting things, but which primary pupils know that they can choose this as a career path? Even in secondary school, only limited aspects of Earth Sciences are to be found split between slim sections of the Geography and Science curricula, and very few schools have the funding, teachers or resources to offer the Geology GCSE. By the time students reach their A Levels, if they realise they wish to pursue Earth Sciences at University, it may be too late because the subject requirements may not have been met. I had the fortune that I came into sixth form knowing that I wanted to pursue Earth Sciences/Geology as I was voraciously into volcanoes, so I chose my A Levels accordingly. For Oxford, these were Maths, Chemistry, Geography and Physics. However, many of my peers came onto the course having simply thought, “What subject could I do by combining these A Levels?” Their approach was a little more retrospect. There is nothing wrong with this, but I think a little more Earth Sciences awareness lower down the academic chain would spark earlier interest. This would surely open-up more opportunities for students to pursue the subject at higher levels, which would, in turn, promote greater study of our one, precious planet that it so desperately needs and deserves.

For adventure and for the Earth,

2 thoughts on “5 key lessons for humanity I learnt studying Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford”