In my previous post, I explored 5 key lessons for humanity I learnt studying Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford. But what is Earth Sciences? And why should you study it? In this post, Part 1 of a two-part series, I’ll answer these questions to dispel some of the confusion surrounding what Earth Sciences is, and why it is a superior, topical subject that should be on your radar.

What is Earth Sciences?

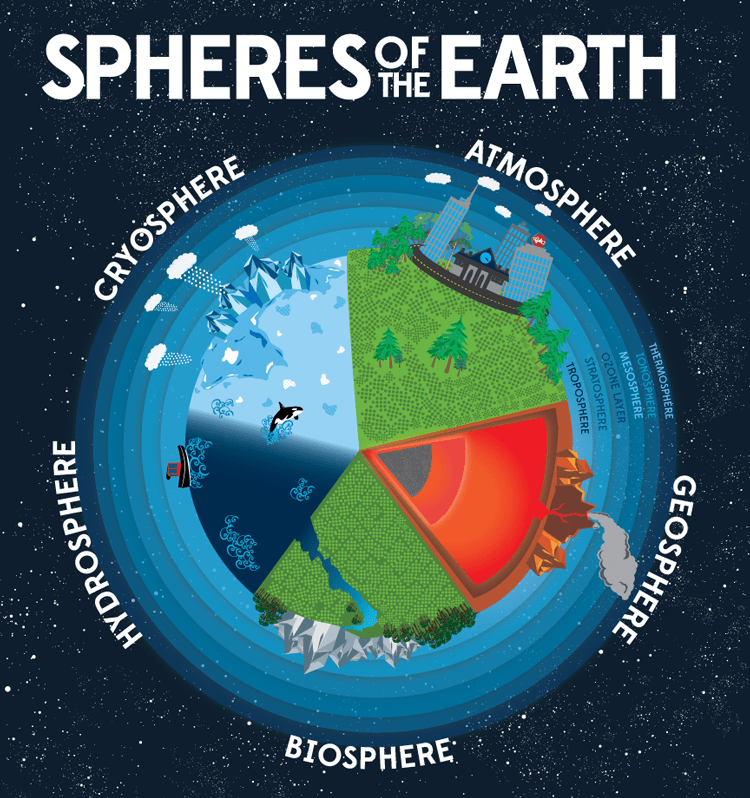

Earth Sciences is a composite subject that welds together Geology and the Natural Sciences (i.e., Physics, Chemistry, Biology, and Maths) as well as tangential Earth-related subdisciplines. Broadly, these can be categorised as concerning either the lithosphere (read: rocks), atmosphere, cryosphere (i.e., ice), hydrosphere, or biosphere. Therefore, Earth Sciences shares some topics with Physical Geography e.g., climate and natural hazards, but envelops less-familiar topics too, and all within a more rigorous, scientific framework across time and space.

Under the Earth Sciences umbrella subdisciplines range across the Natural Sciences spectrum. These subdisciplines can differ greatly and require different skill sets. However, each is needed to obtain a holistic understanding of how Earth works, its composition, and its evolution. Below are some example fields:

Economic Geology/Natural Resources: The study of how earth materials form and may extracted for useful economic, industrial, or human processes. (Cue groaning at the oil, gas, and mining industries.)

Geodesy: The mathematical study of the shape and form of the Earth (fyi, Earth is an ‘oblate spheroid’), and its gravity. Variations in rock density in Earth’s crust, and the changing thickness of the crust in different regions, all influence small-scale changes in Earth’s gravitational field.

Igneous Petrology: The study of igneous rocks i.e., rocks formed by cooling and crystallising magma, either on the surface when it erupts as lava from volcanoes and fissures, or in the subsurface as intrusions, these cooling much more slowly. ‘Ig Pet’ is commonly studied alongside Volcanology.

Geomorphology: The study of geological landforms like basins and mountains, the processes that formed them, and their evolution. This is similar to Physical Geography.

Geochronology: This uses time indicators in rocks to determine Earth chronology. Indicators could be the ratios of radiometric isotopes in their radioactive decay systems, or the evolution of fossil groups within a past environment recorded in the rocks. Geochronology is linked closely with Stratigraphy.

Geodynamics: The geophysical (i.e., maths-heavy) study of dynamical processes occurring within the solid earth, especially its core and mantle.

Metamorphic Petrology: The study of metamorphic rocks, which were once either igneous or sedimentary, and the processes and conditions of metamorphism. ‘Met Pet’ can be especially useful when determining the ages and stages of mountain belt formation.

Mineralogy: Minerals, their composition, and the rocks they occur in. Rocks are essentially made up of mineral components. So, to know your rocks, you need to know your minerals.

Oceanography: The study of Earth’s oceans, split into Physical and Biological components.

Palaeoclimatology: Palaeoclimatologists use proxies to constrain the conditions (geological, atmospheric, oceanic, cryospheric, and biological) of different past environments. Proxies can range from stable isotope ratios in ice cores to species of pollen. Palaeoclimatology is also incredibly important to study to gauge how future climates could look.

Palaeomagnetism: Recovering past geomagnetic fields from magnetically inclined minerals in rocks.

Palaeontology & Palaeobiology: The study of fossils (can include dinosaurs!) and their ecologies.

Planetary Science: Yes, studying the Solar System comes under Earth Sciences’ jurisdiction. Planetary Chemistry performed on very old rocks and meteorites is important for understanding the formation of our planet.

Sedimentary Geology: The study of rocks formed on Earth’s surface from sediments that have been eroded, transported, and deposited in basins and depressions, more often in the oceans, but also on land. Over geological time, accumulations of sediments undergo diagenesis, producing sedimentary rock.

Seismology: The study of earthquakes and how seismic waves travel through the solid earth. It is only through seismology that we know the interior structure of our planet.

Stratigraphy: The study of how rock strata are layered and ordered. Several stratigraphic methods exist. They include biostratigraphy (using fossils), chemostratigraphy (using chemical signatures), chronostratigraphy (using rock ages), lithostratigraphy (using the rocks themselves), and magnetostratigraphy (using the directions of rock magnetisation). Which method is used depends on the rock being investigated. Stratigraphy is very important; get it wrong, and the passage of Earth history becomes disordered.

Volcanology: You guessed it! This is the study of volcanoes, their structure, physical processes, chemistry, occurrence, and effects. My favourite. Volcanology is very often paired with Igneous Petrology.

The Geological Society has mapped-out many of these subdisciplines of Geology/Earth Sciences. You can find more of their degree guidance here.

And one final, fundamental facet of Geology is…

Field work: This can have many aims, but all field studies use geological measurement-making as a basis for quantitatively drawing-up an understanding of a landscape’s geological history. Field trips are fun occasions to engage with Geology hands-, helmets-, and high-vis-on.

I was disappointed to have missed the most exciting of my field trips thanks to Covid-19: field trips to Assynt in north-west Scotland, a 6-week mapping project in Norway, a tectonics trip to Andalusia in southern Spain, and a volcanology and earthquakes trip to Santorini and Athens in Greece. But, I enjoyed earlier field trips to the Welsh west coast in Pembrokeshire; the Isle of Arran (an island in the Firth of Clyde in Scotland), and Dorset and Cornwall in south-west England.

First-year geologists in action on the Isle of Arran in Scotland.

Why should you study Earth Sciences?

There are many reasons why you should study Earth Sciences. This previous post should give you some food for thought given the current climate (pun intended). Alternatively, the breadth of an Earth Sciences course allows you to span a range of scientific outlooks on the natural world, and dapple in the many subdisciplines. Sometimes, this breadth of focus means putting-up with topics that you, perhaps, dislike. But it’s worth it, and necessary, for a holistic understanding of our home planet.

I applied for Earth Sciences with the intention of pursuing Volcanology. Aside from being quite obsessed with volcanoes, for me, these fiery, natural phenomena most strongly demonstrated how dynamic Earth is, so I desired very much to study them.

Course structure

The course structure is both broad and demanding, composed of a diverse range of lecture courses, practicals, tutorials, and field trips at least once a year (pandemic permitting).

The 1st year is principally a Natural Sciences year: fairly generic and mathematically involved, but lectures include some modules in the ‘Fundamentals of Geology’. The 2nd year becomes more focussed with specific disciplines in Earth Sciences like radioisotope geochemistry and metamorphic petrology. The highlight of the 2nd year is that you *should* get to undertake your own mapping project for which you plan-out all the logistics of in a small team that you will spend several weeks in the field with over the summer. (I had very much looked forward to my mapping project in Norway, so was deeply disappointed that Covid-19 disabled that from happening.) In the 3rd year the courses become more scientifically challenging as real-world, geoscience applications are brought to the fore, rather than engaging with generalised, repeatable exercises in Geology. Meanwhile, you have the scope to choose a research topic for your extended essay, which like the rest of 3rd year, has a focus on a problem yet unsolved.

The 4th year is very different. Half of your focus is on preparing and leading the seminar courses, which take the style of scientific debates on current issues in the subject and deconstructing misconceptions. The other half is spent dedicated to your master’s project, a chance to research a question in a field you are really interested in alongside an academic actively working in that field.

For example, I investigated the geochemistry of recent eruptions of the Mt Vesuvius volcano in Italy (I hoped to visit the volcano, but Covid was still throwing its tantrums at the travel industry). Still, I worked in the Earth Sciences Department under the guidance of volcanologist, Prof. David Pyle, who helped me to discern the project’s path. Mine was a petrographical, geochemical project, but yours could be on marine geobiology, mantle physics, icequakes, or meteorites. For many students, including several of my peers, their exciting research experiences in the 4th year lead them into their future careers.

If you would like full details on the current course structure, you can find all the up-to-date course information on the Department of Earth Sciences’ website.

Outlook

Overall, Earth Sciences is an engaging, interdisciplinary course that promotes a deep understanding of the origin and context of our planet, especially at Oxford where the focus is on quantitative study. The rock-solid foundations gained throughout the Oxford course give a strong basis for solving problems in the subject, which can vary from working-through differential equations on rates of glacial retreat, to calculating quantities relating to the alkalinity of the ocean using chemical data. Problems can also be more abstract as in essays and tutorials where you explore more open-ended questions on geological hot-topics like: was the Cambrian Explosion a real geobiological event? What are the mechanisms by which speciation occurs? How did major environments change across the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM)? In this way, Earth Sciences uses our planet as a focal-point, the centroid of a range of complex geological problems for which there may, or may not, be answers. If you value our planet as a system to be studied, enjoy science, and love solving and exploring problems, Earth Sciences may be for you.

So, Earth Sciences. Should you choose it? Hopefully, I have given enough insight into what Earth Sciences involves that anyone interested in using a wide range of observational and quantitative scientific skills in an Earth-based context could say yes to that. Of course, if these reasons have not convinced you, maybe the field trips to magnificent, geological destinations will!

If you want to find out more about the application process, watch this space for Part 2!

Until then, rocks of love,

2 thoughts on “A graduate’s guide to studying Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford, Part 1: what and why?”