Friday, 21st October marked the bicentenary of the 1822 eruption of Mt. Vesuvius and was the inspiration for an interdisciplinary conference I attended at St. Anne’s College in Oxford. From Volcanology to Art to Literature – prose and poetry across the Grand Tour era – Vesuvius experts met from across the world to share illuminating science and ideas on this richly studied volcano. However, and more importantly, Vesuvius 22 highlighted the forgotten contributions of women to pioneering, geological inquiry in the 18th and 19th centuries, and how their examples are still relevant in the 21st century.

Presentations in ‘STEAM’ research fields (not STEM) are somewhat rare. However, on 21st October 2022, Vesuvius 22* brought together under one roof volcanologists, art historians, and experts on the literature surrounding the volcano – brilliant minds to break the imagined barriers between these academic fields.

The volcano science – my connection to Vesuvius

Vesuvius is a unique volcanic system, and yet, in many ways, it also provides a ‘model’ for other volcanoes globally, as my supervisor, volcanologist Prof. David Pyle, discussed in his presentation at the conference. This is partly because of its size – neither too large nor too small to be adequately studied, and its location – easily accessible, especially by boat, close to the Almafi coast on the Italian peninsula in the centre of the Mediterranean. Combined with its historical significance as the volcano that buried Pompeii in 79 AD, these factors mean it is volcanologically well-studied, and can serve as a standard, a comparative point, for other volcanoes. More excitingly for volcanologists, Vesuvius oscillates between producing effusive, basaltic eruptions, and more explosive, chemically evolved eruptions, therefore demonstrating flexibility in its magma chemistry and magmatic processes. These are useful to investigate to aid understanding of similar features and processes at more remote, less well-studied volcanoes.

With this background, earlier this year I carried out my master’s project on reconstructing the eruption timeline over Vesuvius’ most recent active period, 1631 to 1944, working with my supervisor to analyse lava and scoria samples from the 18th and 19th century eruptions (less well-studied, at least scientifically, compared to the bigger, more explosive eruptions of 1631, 1906, and 1944). Specifically, from each eruption in my sample set I selected individual clinopyroxene crystals on which to perform microanalytical techniques (EMPA, SEM, and petrography). Clinopyroxene is a mineral group ubiquitous in Vesuvius lavas that can be used to infer features of the magmatic system beneath the volcano such as how ‘primitive’ batches of magma arising from the mantle are, and the variation in the chemistry of these batches. So, I initially attended the Vesuvius 22 conference to enhance my understanding of the 18th and 19th century eruptions that I’d been studying. Perhaps I might learn something new to add to my research.

Capturing the sublime – Vesuvius in the Arts and Humanities

However, attending the conference was also an opportunity to hear what studies of the volcano in the Arts and Humanities had discovered, and how their results could help the science (and vice versa). As became apparent, the great paintings and prose on Vesuvius during the Romantic era are not only creations commendable in their own right, but they conceal helpful descriptions of individual eruptions of Vesuvius over the 18th and 19th centuries, too.

For example, Prof. Peter Davidson, art historian and curator of the Campion Hall Collection at the University of Oxford, exuberantly discussed how eruptions of Vesuvius had been rendered by the Romantic painters, J.M.W. Turner, Pierre-Jacques Volaire, Joseph Wright of Derby, Giovanni B. Lusieri, and others frequenting the volcano during the Grand Tour era. Prof. Davidson also made myriad references to Sir William Hamilton, the British diplomat, antiquarian, and archaeologist, whose Romantic and scientific voyages for the Royal Society saw him visit Vesuvius more than 70 times, each time documenting the eruptions, often accompanied by sketches and plates by Anglo-Neapolitan artist, Pietro Fabris, under Hamilton’s close, scientific supervision. Over the last few decades, modern volcanologists have enlisted Hamilton’s work to distil the type and variation in Vesuvius’ volcanic activity.

Another example: Prof. Emanuela Tandello, Lecturer in contemporary Italian poetry, revelled on the poetic works of Leopardi and his relation to Monte Vesuvio in ‘La Ginestra’ or ‘The Wild Broom’ / ‘The Flower of the Desert’. With great flamboyance, like the poet Leopardi himself, Prof. Tandello read stanzas and explored both their human, naturalistic, and plausibly accurate, volcanological meaning.

Women of the Romantic and Enlightenment periods – lost observations and interpretations

Much as I enjoyed exploring Vesuvian volcanology and unfurling the period playing out behind the romanticised eruptions, for me, the highlight of the day was delivered by Dr Adelene Buckland, who presented on the geological work performed by women, or lack thereof, during this period. Truth is, the contributions of 18th and 19th century women to ‘STEAM’ fields prior to the late 20th century, are rare, even on phenomena as hyped and revered as Vesuvius. Such works do exist, but the socio-political sphere that then supported only the male half of humanity meant that finding women’s work to promote is an active pursuit for researchers like Dr Buckland.

A senior lecturer in nineteenth-century literature at King’s College London, Dr Buckland is currently exploring female embodiment in scientific observation. The empirical, masculine view in the nineteenth century, and that persists, was one of philosophic fortitude; knowledge was the outcome of physical and mental endurance. Privileged, ‘enlightened’ men like Hamilton climbed the volcano, undeterred by danger, and upheld their dignity. Men bottled-up their senses in the face of the sublime to expand the scientific imagination. What did women do?

To explore this question, Dr Buckland considered two women, both of whom assisted Charles Lyell, the renowned Scottish geologist, on several of his inquiring expeditions, though not to Vesuvius. Maria Graham, while better known as an author of children’s and travel books, was also a member of the Royal Society of Geologists in Edinburgh. She travelled to Chile where she observed an earthquake scientifically, methodically, like the enlightened men. As her observational skills developed, she began to propose geological theories, but her role in Geology was frowned upon. Too speculative, inductive, caught in the crossfire of male intellectual predominance, her work went unpublished.

Secondly, Dr Buckland turned to Charlotte Murchison, wife of the geologist, Roderick Impey Murchison. It is telling that her character is known firstly by her affiliation in marriage, yet Charlotte was an exceptional and meticulous geologist herself. For example, she journeyed with Lyell and her husband on a grand tour of France. While the two men left to go mapping large, geological structures on horseback, Charlotte went fossil hunting, recording ancient animal forms in remarkable detail. Sadly, when their combined work on the Auvergne was submitted to the Royal Society for publishing, Lyell’s paper made no mention of Charlotte Murchison. Charlotte did receive some credit when she worked alongside the respected Lyme Regis fossil hunter, Mary Anning. There, in Dorset, Charlotte made great discoveries on life in the Cretaceous period, but that credit is limited to her field notes, lists, and drawings, no official, published works. Her only saving grace might have been a lack of delimiting references to succumbing to ‘the sublime’ as was the expected response of women to witnessing natural wonders in the nineteenth century.

I found it poignant that women’s contributions to work on Vesuvius, especially artwork, were absent from the conference. Dr Buckland’s allusions to women’s forgotten scientific observations led me to wonder: how would Vesuvius’ history look if it had been written by women? Because while the eruptions themselves would be unchanged, some features might have been overlooked, as evidenced anecdotally by Charlotte Murchison’s diligence in fossil notation that her male friends neglected.

Close of day – contemporary readings in Science and Nature

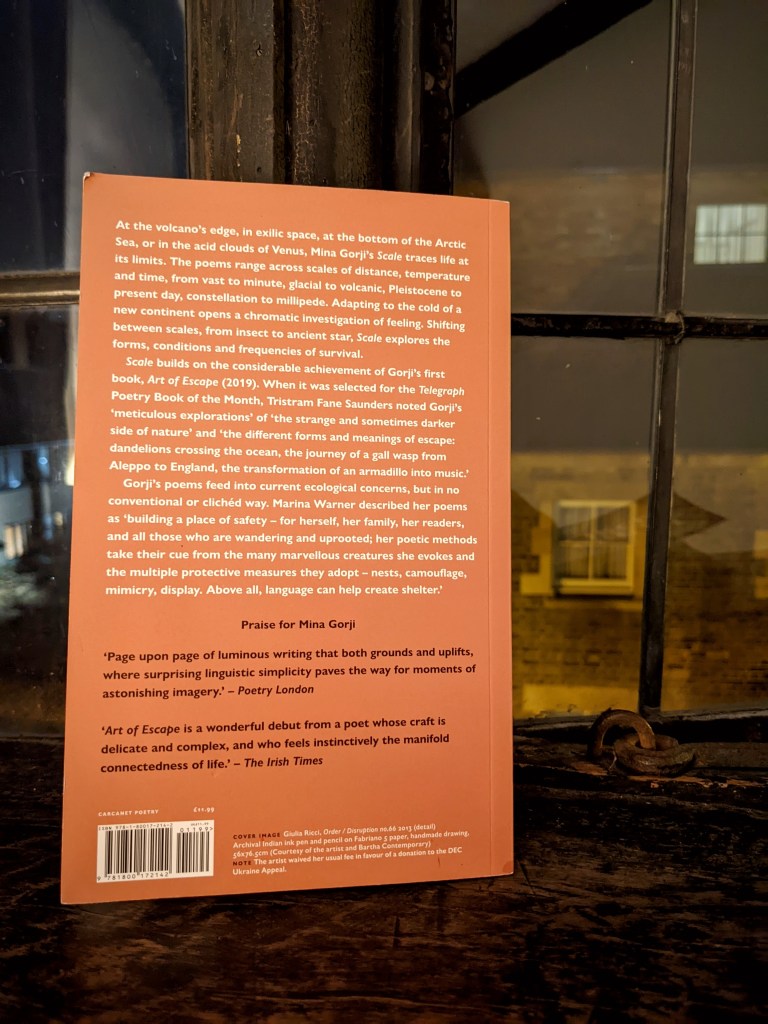

The conference concluded aptly with discussion and readings of contemporary poems of an interdisciplinary nature by David Constatine and Mina Gorji. David’s poems were chilling – he chose to focus on the overriding theme in Science currently, that being climate change. Even in a room of geology and literary experts, the effect was dramatic. But it was Mina’s poems that I really absorbed. Her work is modern and minimalist in style yet encapsulating in its precise command of natural phenomena, sometimes politicised, or understood through cultural references. And, fittingly, many of her poems ponder the undisputable attraction of volcanoes.

Epilogue – an appeal to more women in STEAM

There is so much still to be learnt from volcanoes, even the world’s most studied volcano, Vesuvius. Hence, in 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a report identifying 3 Grand Challenges for Volcanology to address. Thankfully, unlike in the Romantic and Enlightenment periods, we now live in a time when women’s contributions to Volcanology and its Grand Challenges can be recognised, though not in global totality. Like most STEM fields, the more women contributing to developing the field of Volcanology, the wider and more accurately the science will be presented. However, I would argue that encouraging women into STEM and Volcanology is not enough. As I said at the beginning, the Sciences and Arts are not separate. So, I make this an appeal to more women in STEAM fields and following in the footsteps of nineteenth-century pioneers like Maria Graham and Charlotte Murchison.

– Assuredly, a woman in STEAM.

*Full details of the Vesuvius 22 programme can be found at: https://torch.ox.ac.uk/event/vesuvius-22.