I hope I can be forgiven for this delayed update, but the first 3 months of my PhD have been a busy and exciting whirlwind! There have been undoubtedly intense lab days and more methodical office-based ones, but what I did not expect was just how much I would enjoy being back in academia, and especially being back working in my field of Earth Sciences. I hope you will enjoy reading what adventures have befallen me at the outset of my PhD, with plenty more to come.

Month 1

As might be expected, the first month of my PhD journey was split between numerous postgrad inductions, matriculation into the University of St Andrews, and getting set-up in the office ready to begin my project: a 3-to-4-year odyssey researching climate-changing volcanic eruptions of the last millenia. While all quite official on paper, my first month was filled with much excitement as I began processing geochemical data from my first target eruption – the 10th century fissure eruption of Eldgjá in southern Iceland, which I had visited in early August as part of some introductory fieldwork with colleagues at the University of Iceland (you can read a run-down of the field trip here). This also brought the strange joy of reacquainting myself with the bewildering abilities of Microsoft Excel.

But perhaps more importantly, the first month welcomed the much-anticipated beginning of my professional journey working alongside my wonderful supervisory team, led by volcanologist and Principal Research Fellow Dr Will Hutchison, and the truly brilliant climatologist Prof. Andrea Burke. I had the pleasure, too, of meeting all the other PhD students in our office for this academic year, who are collectively tackling a staggering array of problems in Earth and Environmental Sciences – everything from interpretting past climates from meticulous analysis of ancient tree rings; decoding the mysteries of rocks from Mars; what the role of nitrogen is in the Earth’s interior, and what microfossils can tell us about how the ocean cycled CO2 in bygone eras. In beginning my research on comparatively modern volcanism, I have already been made part of a family of scientists who, collectively, endeavour to dive deep into understanding the complexities of Planet Earth.

Moreover, the first month within this community also gave me the pleasure of taking my volcano knowledge and expertise out of the higher education setting and into a high school in inner-city Edinburgh. Alongside our outreach lead Ms Lynn Daley, the St Andrews GEOBUS made the journey over the Queenferry bridge to deliver 3 days of volcano-related demos and workshops, bringing smiles and Vitamin C explosions to a few hundred second-year pupils. Deploying the infrared camera went down very well, too, this being a very useful tool in my supervisor’s volcano monitoring arsenal. For me, having previously worked for a year in a school, I loved being back in this setting and sharing my subject enthusiasm with younger students. Most certainly, I am looking forward to becoming more involved with GEOBUS more over the coming years as my PhD develops.

Month 2

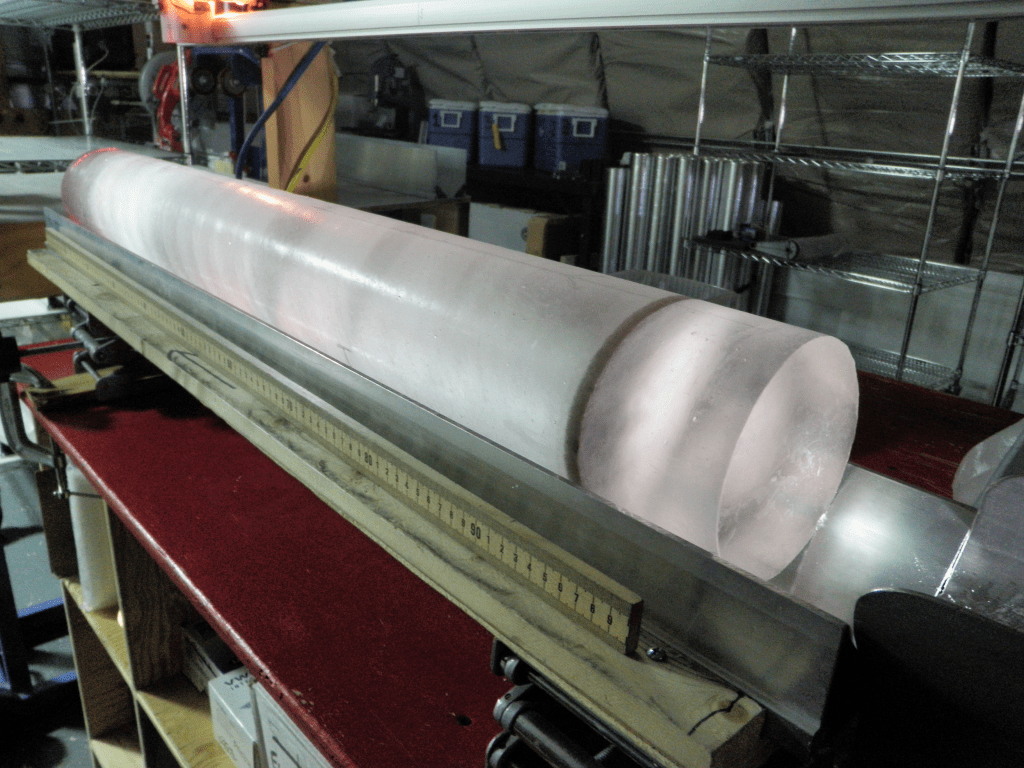

After a month of introductions and familiarising myself with the University, now was the chance to really start work mining the mechanics and chemistry of ‘climate-changing volcanic eruptions’, particularly Icelandic ones. Though Eldgjá served as a starting point, my volcano of real focus would be Askja, a remote caldera volcano in the Northern Volcanic Zone of the central Icelandic highlands. Whilst I’ve yet to visit Askja, my research could already commence using debris from the eruption locked-up in ice cores recovered from Greenland and held in the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at St Andrews. When a volcano erupts with significant explosivity, microscopic rock and mineral fragments and volcanic gases of distinct chemical signature can be transported via the troposphere-lower stratosphere (lower-mid atmosphere), and later deposited, as ‘fall-out’ on the polar ice sheets in annual layers. Detecting these volcanic horizons in ice cores is something my supervisory team in St Andrews have been working on for some time. It’s meticulous work but boasts the potential for fascinating discoveries like this one within the volcanic record. Finding Askja in the record was just the next piece of the puzzle.

In partial contribution of my PhD project, I am tasked with pruning a section of the ice core archive using a series of precision analytical methods in the St Andrews Isotope Group chemistry laboratories. The process began with separating my samples from across the section of bottled ice representing the Askja eruption peak into particulate and aqueous components, before beginning training on the IC. This initial stage using ion chromatography would then allow me to separate ions from fluoride to phosphate within the aqueous samples, and so isolate the sulfate concentrations that I was really interested in, since it is the sulfate concentration within the ice core that is characteristic of volcanic eruptions. Thankfully, as hoped for, the section of Greenland ice core hoped to pertain to the 1875 eruption of Askja did indeed return a sizeable sulfate peak of 130 parts per billion.

“Ion chromatography would allow me to separate ions from fluoride to phosphate within the aqueous samples, and so isolate the sulfate concentrations that I was really interested in, since it is the sulfate concentration within the ice core that is characteristic of volcanic eruptions.”

Having acquired my sulfate data from across the Askja ice core, it was then time to move onto the next segment of my training in ice core climate science: learning the clean lab environment.

Month 3

Migrating from the IC to the clean lab was a baptism by fire (or ice?). Two months later, as I write at the turn of the New Year, the clean lab still bewilders me. For those unaware, a clean lab is ‘a room that is specifically designed to limit the amount of airborne contaminants.’ This means that the lab is kept under constant environmental control, including pressure control, temperature control, and the donning of full hazard suits by all who use it 🙂

After induction of all the many points of danger in the lab, most notably the presence of concentrated hydrofluoric acid, inhalation or ingestion of which can be fatal, I began my lab training with preparing my samples for separation and dilution on the ‘prepfast’ (which performs semi-automated column chemistry), before eventually moving to the multi-collector induction-coupled mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS) or, ‘Neptune’, as it is known in the Isotope Group.

Over the course of November into December 2024, my hours were split between several intense days on the Neptune, seeking to discover what the sulfur isotope composition of each of my samples was, and searching for tephra from the Askja eruption on the SEM (scanning electron microscope), which may have also been preserved in the ice core. I was very grateful over this period for the guidance of our dedicated lab technician Dr Patrick Sudgen, without whom I would have not have landed my preliminary dataset, or indeed achieved anything in the lab. Miraculously, by the time the University began winding down for the Christmas break, I had most of the data I would need to start interpretting the significance of the Askja 1875 eruption in the New Year.

But lab work wasn’t all, there was more. On the side of my sulfur isotope and tephra hunting were various hours of demonstrating in undergraduate geochemistry classes, and professional training with the IAPETUS2 Doctoral Training Programme, which generously funds my PhD. In mid-November, I spent a few days at the University of Stirling meeting my IAPETUS DTP peers and enjoying some good old-fashioned team-building (and spaghetti-and-marshmallow tower-building), as well as a series of workshops in data presentation, programming and thesis writing. Plenty more of this to come as the PhD continues…

In review

As I hope you have gathered from this rather lengthy update, over the past 3 months, I have been having a lot of fun getting into the swing of modern volcano-climate research, and training as an Earth Scientist at St Andrews. Through laboratory techniques, modern methods in analytical chemistry, and various exciting meetings with my supervisory team and lab group along the way, it’s safe to say that a PhD in Earth Sciences is not as much about the rocks, numbers or data as it is about creative thinking, skills development, discovery and collaboration. As a result, I can honestly say that I have loved all that I have been doing in my PhD so far, and I cannot wait for the next stage in the coming semester, and the rest of the academic year – bring on more of the Neptune!

So, until the next time, I hope you are feeling inspired!

One thought on “PhD Adventure Files 003: First 3 months of PhD”